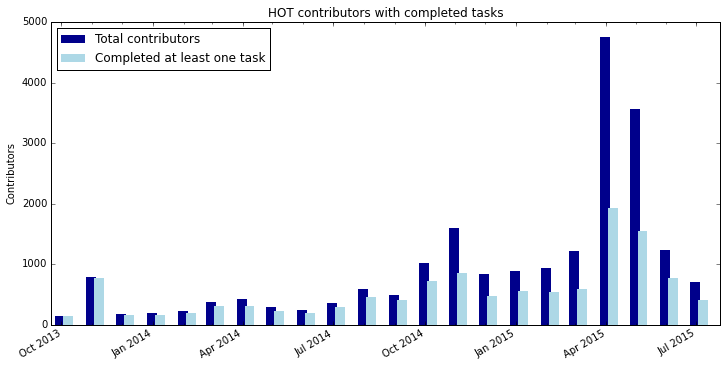

So I completed a PhD on community engagement in HOT and Missing Maps...

Posted by dekstop on 15 September 2019 in English. Last updated on 20 September 2019.… two years ago, and I haven’t even managed to write a diary entry about it. Has it really been that long? I’ve been meaning to post a summary for the longest time, but somehow life got in the way. Fortunately, this week David Garcia and me will host a workshop at the HOT Summit and present a talk at State of the Map in Heidelberg. I’m super excited about both sessions – you should join us if you’re coming! And it became the perfect excuse to dust off my draft for this post, and make sure all the research outcomes are finally assembled in one place.

But let me start in the beginning.

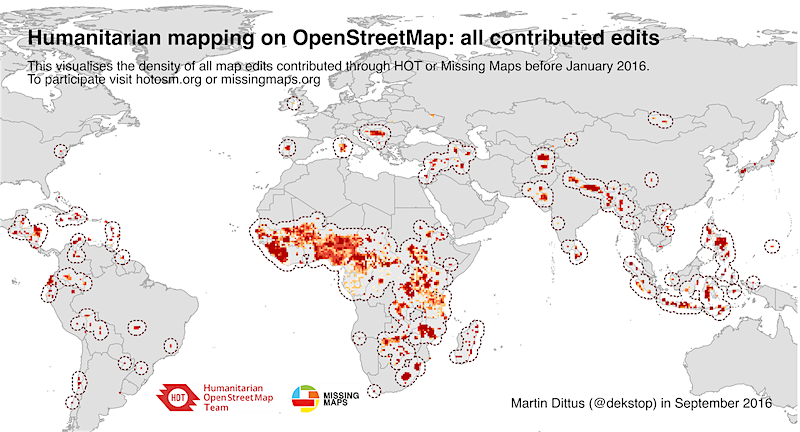

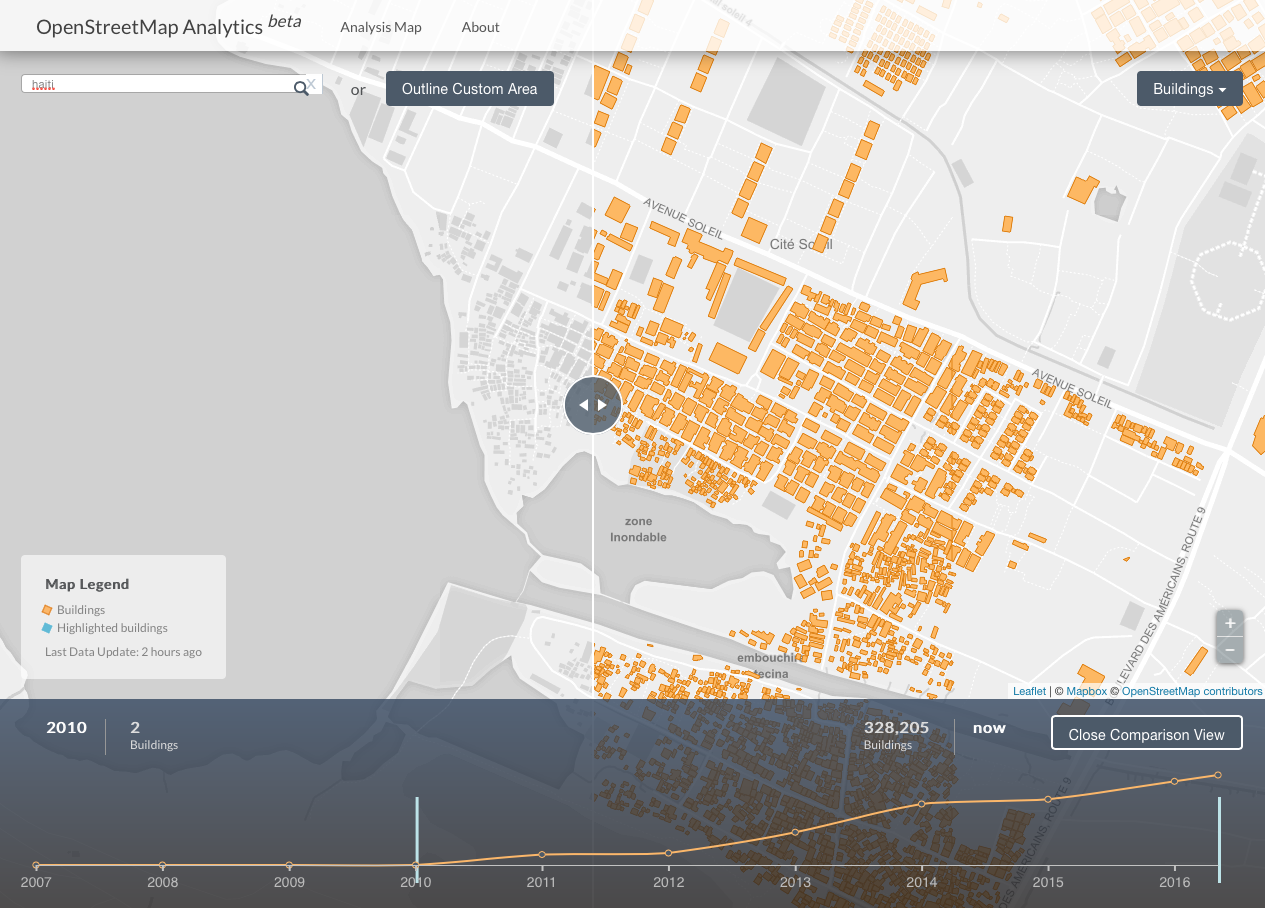

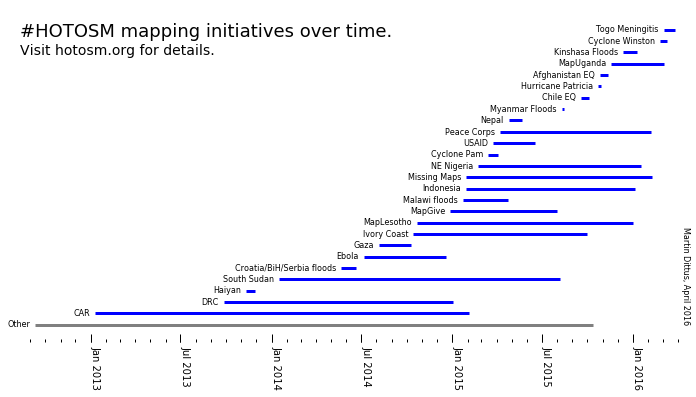

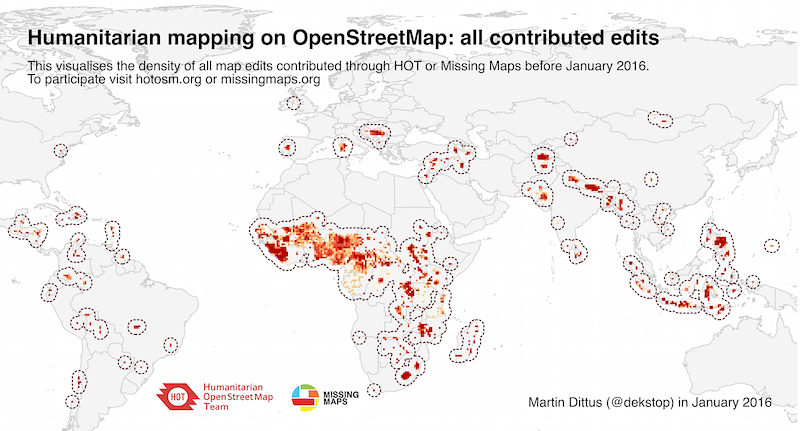

Hallo, my name is Martin Dittus, and between 2014 and 2017 I’ve accompanied HOT and Missing Maps for my PhD on community engagement in humanitarian mapping. We’ve had an amazing time together! During the PhD, we were trying to understand how best to build HOT volunteer capacity online and offline. How can we best train our volunteers so that they are available when needed? What kinds of support can we give them to ensure they don’t drop out early? And the age-old question: are the most highly engaged contributors “born or made”?