Forgotten Heroes

Posted by alexkemp on 23 September 2022 in English. Last updated on 14 October 2022.Arthur Brown

Joseph Bazalgette is rightfully lauded as an accomplished Engineer & heroic in many actions, including in his role as chief engineer of London’s Metropolitan Board of Works, implementing gargantuan sewage works that will have saved millions of Londoner’s lives from the threats of cholera & other water-borne diseases. Few people will realise that there are many similar Victorian-era heroes within Nottingham’s history, and it is likely that even fewer people could name any of them.

Go to this diary entry for more info on any year quoted here.

Today’s diary will commemorate Nottingham’s Borough Surveyor and Engineer Arthur Brown, and underline his achievement in designing & building the 1884 Beck Valley Storm Water Culvert.

The picture above is of the Trent Lane end of the culvert, which is 4.11m x 2.95m (13′ 6″ x 9′ 8″); built with Staffordshire Blue engineering brick below (Victoria Works, Aldridge; waterproof); go to substormflow.com for this & many other very fine views + their story on exploring this culvert.

The picture above is of the Trent Lane end of the culvert, which is 4.11m x 2.95m (13′ 6″ x 9′ 8″); built with Staffordshire Blue engineering brick below (Victoria Works, Aldridge; waterproof); go to substormflow.com for this & many other very fine views + their story on exploring this culvert.

The Engineer

Sources:–

- Born: 21 November 1851

- School: Nottingham High School (Free Grammar, Stoney Street; in 1868 that school transferred to Waverley Mount, Forest Road)

- Age 16 (1867): articled to Marriott Ogle Tarbotton, the Borough Engineer

- Age 23 (1874): promoted to Deputy following collaboration on Trent + Gunthorpe Bridge (the 1875 bridge was replaced in 1927)

- Age 28 (1880): promoted to Borough Surveyor and Engineer (Tarbotton had become Engineer at the newly-purchased Nottingham Waterworks Company)

(over the next 40 years Brown transformed Nottingham)

(following are highlights of just some of his projects): - 1880: Gregory Boulevard, Radford Boulevard, Lenton Boulevard + Castle Boulevard built

- 1883 March 3: report on defects at University College, opened 30 June 1881

- 1884 Aug 7: Beck Valley Storm Water Culvert officially opened (begun 1883, completed 1885)

- 1885: Plans for a new Cattle Market in the East Croft

- 1889: King Street and Queen Street built (redevelopment of The Rookeries)

- 1894

- May 8: Victoria Park opened (former Bath Street Recreation Ground)

- September 18: Construction of 1ˢᵗ Electricity Power Station on the corner of Talbot Street & Hanley Street (only a Substation remains) (wiki).

- 1896 June 30: Victoria Baths (former Sneinton Baths) redeveloped

- 1899 September 11: Following a trip to the USA to research electric trams, Brown (Borough Engineer) + Herbert Talbot (Electrical Engineer) make a report to the Council. The core of the issue is whether to use electrified ground rails or overhead lines. They state their personal preference to be for an underground conduit system, but that both the British weather + local ground conditions make such a system impractical (more on this in the next section).

- 1900 Development of the entire Victoria Embankment

- 1901 Start Date for 2nd Electricity Power Station on St Ann’s Well Road (at this stage the stations primarily are to power the new Electric Trams).

- 1902 Bulcote Corporation Model Farm designed & constructed, including laying 150 miles of drains (Grade Ⅱ listed).

- 1904 Improvements to the Carrington Street Canal Bridge

The Storm Water Culvert

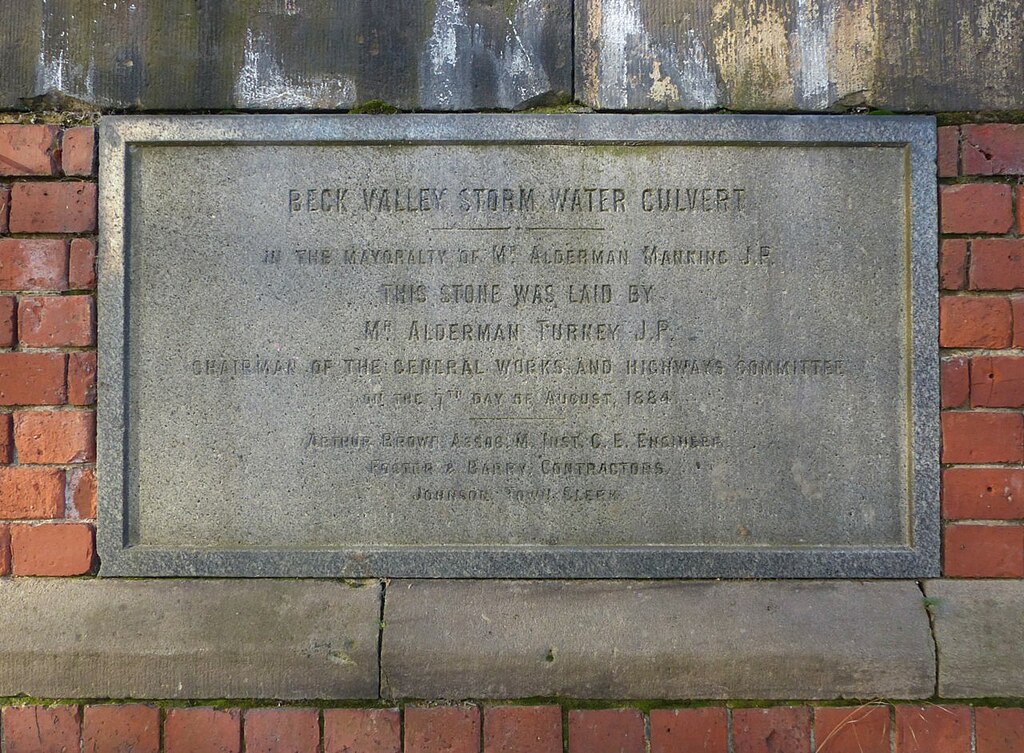

Beck Valley Storm Water Culvert foundation stone

Beck Valley Storm Water Culvert foundation stone

cc-by-sa/2.0 - © Alan Murray-Rust - geograph.org.uk/p/7041196

The Old Beck Sewer

Sources:–

There are lots & lots of sites with excellent reports on walking through this culvert, but there is something that I need to debunk at the outset about all of them:– they all conflate the Old Beck Sewer & the Beck Valley Storm Culvert and, to the best of my knowledge & research, the two are NOT connected.

- An ancient spring originated near (what is now) the junction of Kildare Road with The Wells Road, and flowed down the valley of St. Ann’s towards Nottingham Town. There is every chance that, through historical aeons, that that stream actually carved out the valley that it coursed through.

- In more ancient maps that stream is called “The Bek”

- In the 1820 map by H. Wild and T. H. Smith it is called the “River Beck” & still runs through the town until it empties into the River Leen at East Croft, and thence into the River Trent.

- In the 1862 map by Edward W. Salmon it has already been culverted (it is known as the “Old Beck Sewer” (OBS), though I have not yet found any full mapping for it).

- The 1883 plans (see MSS:R/HR/3/1/25) produced by Arthur Brown show that the Storm Culvert met the OBS at Cathcart Street but did NOT join with it (Cathcart was demolished in the 1960s; it was opposite Southampton Street).

- The 1900 plans (see MSS:R/HR/1/7/196) produced by Arthur Brown show the Storm Culvert being extended up from Cathcart to where the spring originates but still does not indicate any join between the two systems.

Initially the river was simply covered over, and council workers kept getting called out as the stream kept getting blocked by rubbish (or worse), so eventually a proper OBS culvert needed to be built. The 1861 Map produced by Frederick Jackson (NA: CA 8212) shows that culvert on the north-side of St Ann’s Well Road, and that is accurate up to the 5-ways junction (see below).

The 1883 plans showed that the OBS was 2′ 6″ diameter & was siphoned around the Storm Culvert and then continued in it’s original track, side-by-side with the Storm Culvert. Meanwhile, a conventional sewer had a track on the south side of the street.

There was a major 5-street junction at that time, at the point in the modern roads where St Ann’s Well Road turns south (see Northumberland Road):–

- Alfred Street South

- Alfred Street Central

- Union Road

- St Ann’s Well Road (2 roads)

The Storm Culvert + OBS crossed over to the other side of the road at the junction, and in addition the Storm Culvert was increased from 6′ 9″ to 9′ 0″ diameter.

When the Storm Culvert reached the North Wall of St Mary’s Cemetery (which at that time extended all the way to the street) it turned to the east & crossed the cemetery whilst the OBS continued down the street.

The Beck Valley Storm Culvert

You will read above that on September 11 1899 Brown & Talbot made a report to the council on the reasons for their proposal for overhead lines for the electric trams rather than underground conduits. What follows now are the extraordinary reasons for this astonishing storm culvert, including some details from that report:–

- During the era of the super-continent Pangea the UK & it’s near-neighbours was under an ocean, near the equator & opposite the mouth of a huge river much in nature to the modern Amazon. That led to the deposition of alternating layers of clay & sandstone that cloak all of Nottingham.

- Clay is impervious to water, whilst sandstone is water-permeable, and that causes such landscapes to be prone to springs, and also to flooding due to surface-water runoff.

- The UK sits halfway between cold-air masses that originate at the North Pole & warm-air masses that originate at the equator. That is responsible for the UK both suffering more tornadoes than any other country & also being prone to Flash Floods (I’ve experienced the latter dozens of times myself).

- Until 1845 everything north & west of Brook Street was part of Clay Field and could not be built upon as it was Common Land (and yes, Brook Street is where the River Beck ran).

- After the 1845 Inclosure Act St Ann’s Well Road is a steeply-sloped valley running through newly-populated streets. The flash-floods now no longer runoff just the clay, but also off tarmacadam on both those hills.

- In his 1899 report, Brown & Talbot spoke of the way that, after heavy showers, water on Mansfield Road near the Grosvenor Hotel would reach 12″ (30cm) deep, water spread from kerb to kerb on St Ann’s Well Road, and that many other roads also suffered flooding.

Such flooding threatened the viability of the expansion of the town. Something needs to be done! The Beck Valley Storm Water Culvert was the response, and you can get some idea of the magnitude of the problem by the size of the culvert in the picture at top.

The Navigators

My research on these culverts was made on 6ᵗʰ July 2022 at the Manuscripts and Special Collections (MSS) department of Nottingham University, Lenton Lane, and I was blown away at the detail & quality of the work put into the 26 sets of engineering drawings archived by the MSS. These were full-size high-quality Drawing Paper (almost certainly each Arch E), backed with linen, and gathered into a continuous roll of 104′ (31.7m) of architectural x-sections of every pipe, section & joins that would be encountered by the pipe-layers from Trent Road to Cathcart Street. A truly stupendous piece of work, and it blew me away to experience it.

But, what about the Navvies?

(Picture obtained from & © Railway Museum)

(Picture obtained from & © Railway Museum)

So, what is a Navvy?

Wikipedia says:–

“Navvy, a clipping of navigator (UK) or navigational engineer (US), is particularly applied to describe the manual labourers working on major civil engineering projects”

However, that definition misses a high-status feature of the navvies that worked in Nottingham. Digging a culvert through a road is one thing, but having the ability to navigate a tunnel from the bottom of one end of a hill to the other end and to emerge exactly where your employer needs it to emerge is another. Nottingham was full of both sets of people.

One Set of People

1818: A man within a canal warehouse named Musson decided to drop a hot cinder onto a little spilt gunpowder “to see what it would do”. 21 kegs (1 ton total) barrels of gunpowder were stored all around him whilst in transit from Gainsborough for use in the Derbyshire mines, and one of them had been damaged whilst being moved. Boats were destroyed, buildings damaged, and Musson was blown 126 yards (115m) by the blast.

Probably not the sort of person that you would want within your tunnelling gang.

The Other Set of People

There was already over 100 years of continuous navigating experience gained within Nottingham before Brown ever began his Storm Water enterprise. I do not want to take a millimetre of glory away from Brown — as you can see here he estimated the job at £38,000 GBP (£5,135,536 in 2022), and brought it in at £28,000 GBP (£3,784,079 in 2022), and how many infrastructure projects can say that today — but without the skilled workforce he could not have even started.

- Canals:

- 1760 Construction began on Nottingham Canal (completed 1796)

- Trains:

- 1839 Midland Railway (MR) open a station terminus in the town west of Carrington Street

- 1889 Nottingham Suburban Railway opened

- 1900 Victoria Station opened

- Coal Mines:

- 1947 49 collieries in Nottinghamshire when the coal industry was nationalised.

- 1870 Clifton Pit is opened (the exploratory pit was sunk in 1870).

- Tunnels of Nottingham

The Statistics

Here are the relevant stats, drawn from a newspaper article at the time:–

- Max estimated flow: 54,941 cubic-feet/minute (1,556 m³/minute)

(based on max 14 inches of rain received in 30 minutes) - Total length: 10,750 ft (2.04 miles / 3.28 km)

- Estimated cost: £38,000 GBP (£5,135,536 in 2022)

- Actual cost: £28,000 GBP (£3,784,079 in 2022)

- Soil excavated: 50,000 yds³ (38,228 m³)

- Concrete used: 80,000 yds³ (61,164 m³)

- Bricks used: 4.5 million

- Cement used: 12,000 bags

- Lias Lime used: 600 tons (544 metric tons)

(this is hydraulic lime, concrete that can set under water) - Contractors: Messrs Foster & Barry

Discussion